Oomingmak - The Bearded One

Article and photos by Dr. Wayne Lynch

December 8, 2013

Musk Ox in defense formation

Some of my fondest memories of arctic wildlife are so vivid that it seems I can still feel the wind ruffling my hair and hear the comforting songs of familiar tundra birds decades after the moment has passed. Such is my remembrance of a playful herd of muskoxen grazing beside a swollen stream on Banks Island in the Northwest Territories. It was the height of summer and the living was easy for these shaggy northern beasts. They were drawn to the streamside by the lush green sedges and for over an hour I watched them feeding quietly. Suddenly one of the yearlings in the herd waded into the shallows and began to splash and jump in circles. It was soon joined by a second yearling and an adult female. All three of them, each on its own, tossed their heads, twisted, pawed and whirled around as if infected with an irrepressible glee. The apparent joy of the moment brought an embarrassing tear to my eye and I wiped it away before others could see how I was foolishly stirred by such a simple event in nature. The exuberance of the moment was over in less than a minute and soon afterwards the muskoxen quietly forded the stream and wandered out of sight. Even now as I write these words half a lifetime later I struggle to keep from crying again as I recall the wonderful deep feelings these animals evoke in me.

The muskoxen, like no other animal, symbolizes the tenacity of arctic life. Today roughly 160,000 of these magnificent creatures, about 85 per cent of the total world population, eke out an existence in the northern hinterlands of Canada. For muskoxen, surviving the climatic extremes of the Arctic has always been a challenge. The oldest fossils of the modern day muskox are from Germany and are estimated to be somewhere around a million years old. Muskoxen spread from Asia into North America across the Bering Land Bridge between 250,000 and 150,000 years ago. From the beginning, they inhabited lands with long, cold winters and for that they are admirably adapted.

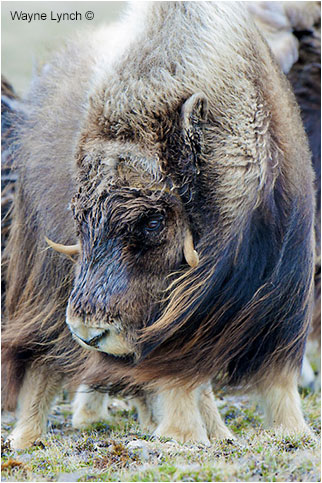

Muskoxen Bull

Biologists define an adaptation as a process by which a species becomes suited to its environment. The muskox has adaptations in two big areas: its body design and its behaviour. One time when I was stranded with an Inuvialuit family on Banks Island, NWT I slept outside on a rocky beach under a furry muskox hide after arctic winds ripped and flattened my tent. I can attest to the weight and warmth of the animal’s hide. A muskox’s pelt is composed of an outer layer of long, thick guard hairs that hide an underwool of fine fur.

Muskoxen bull, cow and calf

Muskoxen calf

The guard hairs, which can be up to 55 cm (22 in) in length, hang like a fluttering skirt around the muskox’s legs; an effective barrier against the icy penetration of the wind. The wool underneath is a thick insulating mat of extremely fine hairs, some of the finest in the animal kingdom; softer in fact than camel hair or cashmere. Only the hair of the vicuna, a relative of the camel that lives in the high Andes of South America, is finer. Human hair by comparison averages four to six times thicker than muskox wool.

|

|

A warm pelt is vital if you live, as muskoxen do, in a world dominated by six to eight months of winter where temperatures can plummet to -40°C (-40°F) for weeks at a time. Often in an idle moment of strolling on the tundra I have plucked some molted wool that was snagged on a willow bush and cupped it in my hands to feel the warmth. Each time I do, I’m surprised by the extraordinary heat reflecting ability of the ball of hair.

Joel Allen, an American scientist who lived a century ago, might have been thinking of the muskox when he formulated the theory that is now known as Allen’s Rule. Allen observed that animals living in cold climates have short ears, tails, legs and snouts. All of these characteristics reduce an animal’s surface area and thus lessen the body heat it loses to a cold environment. The muskox fits the pattern perfectly. Its legs are short and largely hidden behind a curtain of thick fur, its small ears are nestled in a mat of dense wool, and its tail is so tiny as to be invisible.

|

|

|

|

When it comes to behavioural adaptations the muskox has several that serve it well. Its principle diet consists of sedges and willows and when feeding the muskox moves slowly and deliberately, thus conserving energy in an environment where food can be scarce and poor in quality. When there is snow on the ground the animal uses its nose to sniff for food and then uncovers it by pawing with its broad front hooves. If the snow is crusted and hard a muskox will use its chin like a jackhammer to break through the surface, exposing the frozen stems and leaves underneath.

Muskoxen Herd - Defense Formation

Living in groups is a common anti-predator strategy, and muskoxen have adopted this social structure, frequently living in herds numbering from 5 to 50. An obvious benefit of living among others is that an individual surrounds itself with tasty neighbours which theoretically lessens the risk to it of being targeted by a hungry predator. Muskoxen derive another benefit from living in groups, they can mount a collective defense if threatened by wolves or bears or humans. When huddled shoulder to shoulder, a herd of adult muskoxen is a dangerous and formidable phalanx of might and hardened horns - an armoury of lethal weaponry. Imprudent wolves have been gored and killed.

Muskoxen Bulls

Muskoxen Herd

Alhough predators, both human and non-human, can influence muskox survival most researchers believe that climate is the ultimate controller of the animal’s destiny. Cold, dry winter conditions with light snowfall benefit the beasts whereas warm winter weather and freezing rain can turn the snowy tundra into cement and muskoxen starve as a result. One winter on Melville Island,Nunavut, 70 per cent of the muskoxen died of starvation when unseasonable weather conspired to lock their food under a layer of ice.

Young Muskox

No one is certain what the future holds for the muskox and its arctic world. A 2008 report from the Government of Canada entitled From Impacts to Adaptations: Canada in a Changing Climate predicted a warmer and wetter Arctic in the decades to come. Scientists expect that these changes may directly affect the nutritive value of grasses and sedges and thus influence muskoxen, as well as caribou. Wetter summer conditions may increase harassment by insects which in turn can interrupt vital summer feeding so that muskoxen end up in poorer condition and less likely to successfully raise offspring. Winter die-offs could also increase when heavy snowfalls combine with periods of melting and icing. In Canada, muskoxen are hunted as trophies and subsistence game, and also attract thousands of tourists and photographers. With the changing climate added vigilance is necessary to ensure that these hardy survivors remain part of Canada’s wild future.

A stylized muskox has been my business logo since I began as a fulltime freelance nature writer and wildlife photographer more than 34 years ago. It was the animals' dogged tenacity that I thought I would need to survive in this business. I was right. Over the years I haved photographed muskoxen in numerous locations in the Arctic from Greenland to Russia, but my favorite location is still the Canadian Arctic. This past summer I went north again, to Victoria Island, Nunavut to photograph these animals that are so special to me. The experience was great as always and confirmed that three decades ago I chose the right symbol to follow.

|

Bio: Dr. Lynch is a popular guest lecturer and an award-winning science writer. His books cover a wide range of subjects, including: the biology and behaviour of owls, penguins and northern bears; arctic, boreal and grassland ecology; and the lives of prairie birds and mountain wildlife. He is a fellow of the internationally recognized Explorers Club - a select group of scientists, eminent explorers and distinguished persons, noteworthy for their contributions to world knowledge and exploration. He is also an elected Fellow of the prestigious Arctic Institute of North America. Dr. Wayne Lynch E-mail: lynchandlang@shaw.ca

|

Sources#1 Muskoxen, J. S. Tener, Dept. of Northern Affairs & Natural Resources, Canadian Wildlife Service Ottawa, 1965. #2 Muskoxen of Polar Bear Pass, David Gray, Fitzhenry and Whiteside, Toronto, 1987. #3 Back From the Brink - Road to Muskox Conservation in the NWT, William Barr, Arctic Institute of North America, University of Calgary, Calgary, 1991. #4 Muskoxen and Their Hunters, Peter Lent, University of Oklahoma Press, Norman, 1999. #5 Muskox (Ovibos moschatus), Anne Gunn and Jan Adamczewski, p1076-1094 In Wild Mammals of North America - Biology, Management & Conservation, 2nd Edition, Edited by Feldhammer et al, Johns Hopkins University Press, Baltimore, 2003.

[ Top ] |